The Granai Airstrike: On May 4th 2009, a small village in Farah Province in the west of Afghanistan was rocked by a seven-hour long conflict between ISAF and ANSF troops and suspected Taliban militants. The struggle culminated in an airstrike campaign involving at least four strikes by aerial bombers, the last of which are believed to have killed up to 140 Afghani civilians (figures are disputed).

A Pentagon report following an investigation

and military inquiry into the incident claims that F-18 fighters carried out

the first strike that only killed insurgents, and not civilians; however, it

was the subsequent attacks by an Air Force B-1 bomber, which dropped five 500

pound bombs and two 2,000 pound bombs onto the compound, which are believed to

have caused the civilian fatalities. According to the report, the military

personnel behind the strikes failed to discern whether Afghan civilians were in

the compound before carrying out the attack after tracking suspected Taliban

fighters into the building, in a manner that deviated from the established

rules that were designed to prevent these incidents. The

investigation points most clearly to one of the raids carried out by the B-1

Bomber, which, after being cleared to attack Taliban fighters, had had to

circle back to its position but failed to reconfirm a positive identification

of the target after this delay. Afghani civilian witnesses make a claim echoed

in the inquiry that it is possible that the militants identified as being at

the site of the attack had left, or civilians had entered during the time that

the strike was delayed.

|

| Manuel Balce Ceneta/Associated Press |

”American success in Afghanistan should be measured by the number of Afghans shielded from violence, not the number of enemy fighters killed.” LieutenantGeneral Stanley McChrystal testified before a Senate Armed Services Committee, saying that high numbers of casualties that fostered civilian resentment amongst Afghani citizens would be detrimental to American credibility in the region. Full hearing at http://www.c-span.org/video/?286758-1/military-nominations-hearing

General McChrystal’s tactical directives: in response to the Granai airstrike, Lieutenant General Stanley McChrystal issued a list of new “tactical directives” as a means of discouraging ground troops from calling in air support when under fire from militants in heavily populated areas. These directives are just one in a line of similarly issued directives issued following similar attacks in Azizabad, and preceding the one in Kuzud just five months later. The directives issued by McChrystal was for US forces to ‘disengage’ and leave populated areas where they have come under fire from militants operating from civilian occupied buildings. Exceptions are available for US, NATO and Afghan forces in imminent danger, in which cases air power is reserved to provide cover, facilitate their escape, or to remove wounded troops from the area. McChrystal’s exception clause to the prohibition of air crew use in populated areas is a means of addressing the difficulties of US soldiers who must restrict the force used in civilian areas whilst trying to protect their own troops under fire from insurgents in these areas.

According to the Pentagon’s report, the strikes

likely to have caused the casualties would have been prohibited by the new

directives issued by McChrystal as the aim of the strikes was to target

militants in the area rather than to allow for the safe evacuation of military

forces.

“Popular support is the deciding factor

in this fight”

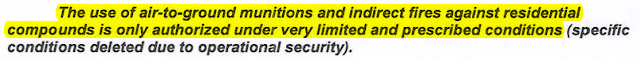

The declassified sections of

McChrystal’s tactical directives constantly reiterates the importance of

winning the popular support of the local population as the key aspect of

winning counterinsurgency campaigns. The basis of Neta Crawford’s moral argument on

the discourse used to conceptualise civilian deaths as collateral damage in

military objectives is that military leadership continues to consider the

protection of local non-combatants as “another tool employed in the service of

winning a war”, and by framing the aim in this way, contradicts the purpose of

civilian protection, making it inherently unstable. There are remarkable

similarities between the directives McChrystal issued after Granai (fig. 1-3)

and those issued by previous US and NATO commander General David McKiernan (fig. 4-5):

|

| Fig 1 (McChrystal, 2009, on the importance of local support) |

|

| Fig 2 (McChrystal, on proportional violence instrumentalising civilian support) |

|

| Fig 3 (McChrystal, on restricted use of violence in residential areas) |

|

| Fig 4 (McKiernan, 2008, on the importance of local support) |

|

| Fig 5 (McKiernan, on restricting violence in civilian areas) |

General McChrystal emphasises the need

to make the principle of civilian protection central to the military’s

objectives, in a bid to reduce civilian casualties. Both McChrystal

and McKiernan constantly reiterate the need to protect civilians in Afghanistan

as a necessary aspect of winning the war through local support. How

effective can their directives be, considering the

strike in Kunduz barely five months later? The Kunduz strike

resulted in further directives issued to control the use

of force in civilian areas, making it obvious that perceiving civilian lives as

instrumental to the wider war effort, rather than inherently valuable, has

prevented effective limits to the use of force in civilian populated areas. The

instrumental calculative framing of civilian deaths as collateral damage is the

most obvious indicator of this, and the idea of military necessity is still

clearly pervasive in on the ground judgements of uses of force.

What this shows is, as Crawford puts

it, the inevitability or normalised view of civilian deaths in

counterinsurgency operations. Responsibility for civilian deaths is delineated

to an individualised level (which she states is shaped by the institutions of

war-making), shown not only through the Pentagon’s report pointing only to the

actions of the B-1 bomber rather than the erroneous misuse of airstrikes as a

whole, but with an erasure of organisational responsibility at the higher

levels of military planning for the deaths that occur because of the way in

which civilian deaths are made a systemic, normalised part of counterinsurgency

operations. When this normalisation occurs at organisational levels, inherent

in the action of war planning is the fact that collateral damage is foreseeable

and adjustable. The “rules of engagement” that troops are expected to abide by

are not contravened when civilian deaths occur; rather, they are a consequence

of these rules. The contraventions are said to occur where there are higher

numbers of casualties, but no deaths are not expected.

The attacks and subsequent military

responses show two things: civilian deaths are still perceived as an inevitable

part of COIN campaigns; and despite efforts to reduce casualty rates this

conceptualisation means there is lesser value placed on the lives of civilians,

and the fragmentary orders (FRAGOs) the military produces reflect the

fragmented, instrumental perception of civilian life in Afghanistan.

By Aneesha Parmar